Pakistani engineer builds brain-controlled bionic hands at fraction of global cost

From child amputees to injured soldiers and terror-attack survivors, Usama Khan’s locally built technology is transforming lives

By Akhtar Pathan

KARACHI, Pakistan (MNTV) — When Usama Khan speaks about technology, he does not begin with circuits or code. He begins with dignity. A biomedical engineer based in Karachi, Khan has developed Pakistan’s first brain-controlled bionic hands — devices he says are not merely mechanical replacements, but tools to restore confidence, independence and life itself.

Priced at around 500,000 Pakistani rupees (approx. $1784), the bionic hands cost roughly one-tenth of similar devices available internationally, which often exceed Rs5 million. Despite their affordability, the hands are among the most advanced in the region, offering multi-grip functionality and neural control that Khan says even regional competitors have yet to achieve.

“This technology is not just about limbs,” he says. “It is about restoring dignity, confidence and life.”

Khan’s work sits at the intersection of engineering and humanity — a space that first drew him toward biomedical engineering as a student. Unlike conventional engineering disciplines, biomedical engineering connects technology directly with the human body, from hospital machinery to life-support systems.

As a student, Khan worked on several practical projects, including a specially designed spoon for people with deformed hands. The spoon could move freely from the back while remaining stable at the front, enabling users to eat independently. The project was modest, but it revealed something more significant: Pakistan lacked access to advanced prosthetic technology.

Even as recently as 2019, locally available prosthetics were largely limited to basic open-and-close mechanisms. Determined to address this gap, Khan began focusing his skills on developing a bionic arm suited to local needs — technologically advanced, yet affordable.

A defining moment

The project became a mission during its first patient trial. The recipient, Shahzad, had lost his arm to cancer. When he used the device for the first time, his reaction transformed Khan’s work.

“Seeing his joy changed everything,” Khan recalls. “It was no longer just an engineering project.”

Since then, more than 100 people have received bionic arms through Khan’s technology. In a country where an estimated one million people live without a hand or foot, he describes the impact as nothing short of transformative.

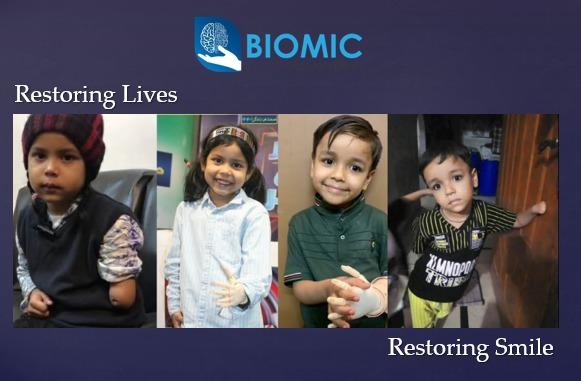

For children in particular, early access can be life-altering. Khan says that when a child receives a bionic hand at a young age, the device becomes part of their identity rather than a reminder of loss. “Instead of feeling incomplete, the child grows up confident — seeing themselves as special.”

Stories behind the technology

Among the recipients is Mishkatullah, a police officer from Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. During a terrorist attack, he fought back and forced the attackers to flee. As they escaped, they hurled a grenade that shattered his arm and it had to be amputated later from the shoulder joint.

While international options were financially out of reach, Khan’s team provided him the most advanced version of the bionic arm with automatic elbow joint (Biomic V2.1) they had developed so far and that too at a fraction of the price in the global market.

Another complex case involved a young man from Iraq who lost both arms in an electric shock. After being quoted nearly Rs50 million abroad, he traveled to Pakistan. Khan’s team provided a full bionic system — including shoulder and elbow joints — for about Rs2 million. Today, the man can eat, drink and live independently.

How the system works

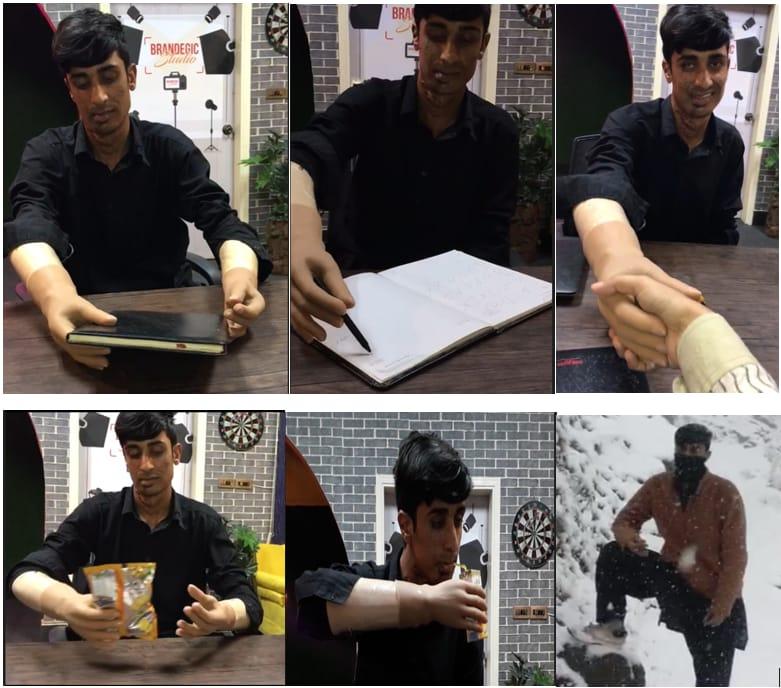

The most advanced model developed by Khan’s team, the Biomic Hand Version 2.1, supports multiple grips — including open-close, victory sign, typing grip, hook grip, thumbs-up and index-pointing. All movements are controlled through biological signals.

Special sensors attached to the body function much like ECG electrodes. Instead of reading heart activity, they detect neural or muscle signals. When the brain sends a command to move the hand, the sensors capture the signal, filter noise, amplify relevant data and process it through machine-learning and neural-network classifiers. The system then translates the signal into movement.

For people born without hands, the process requires additional training. Users are taught to imagine movements, gradually training muscles and neural pathways. Over time, the system learns to interpret these signals accurately. Each device is customized — both hardware and software — according to the user’s biological signals.

Beyond basic movement

Earlier prosthetics in Pakistan were limited to simple movements. Khan’s innovation allows users to perform daily tasks such as typing, switching appliances on and off, lifting bags, opening doors and even performing religious gestures during prayer.

This level of functionality was previously unavailable locally because classifying brain signals is exceptionally complex. Neural patterns vary from person to person, requiring individualized calibration and extensive data processing.

The psychological impact has been profound. Khan says many recipients had lost confidence — some had even attempted suicide after their accidents. With the bionic arm, many returned to work, regained independence and resumed normal lives.

Below-the-elbow users can type, write exams, ride motorcycles, lift up to five kilograms and play sports. One student, Abdul Haseeb, who lost both hands below the elbow, learned to write again and successfully appeared in his FSC examinations using Biomic hands.

Competing on global stage

Globally, advanced bionic technology exists in countries such as the United States and Germany, but costs remain prohibitively high. China has developed limited multi-grip systems, while Khan says Indian companies largely rely on switch-based prosthetics rather than true brain-controlled devices.

After five years of development, Khan says his goal is to compete globally. The next phase is individual finger control and full synchronization with brain signals — a hand that moves as naturally as its biological counterpart.

Expanding to legs and children

In addition to hands, Khan’s team has begun developing prosthetic legs. This year alone, more than 50 prosthetic legs with knee and ankle movement have been fitted, enabling elderly and accident victims to walk independently again. Unlike arms, these devices are primarily mechanical, as brain control is not essential for basic leg movement.

The team also provides bionic arms to children as young as three or four. Early intervention, Khan says, is critical for mental health and confidence. One four-year-old girl, Iqra, was fitted with a bionic arm that controls both elbow and hand — a rarity at such a young age.

As children grow, only specific parts need replacement, while the core system remains intact. The devices are rechargeable, last a full day on a one-to-two-hour charge and are designed for long-term use, with batteries typically lasting three years.

Making technology accessible

Affordability remains central to the project. Khan works with NGOs, zakat-eligible programs, installment plans and private donors to ensure financial hardship does not bar access to the technology.

Biomic Engineering, his Karachi-based company, operates from the National Incubation Center. Patients arrive from across Pakistan and abroad. Government institutions, including the Pakistan Army, have also engaged with the company, and bionic arms have been supplied to injured soldiers and police personnel.

The company’s name reflects its mission: “Bio” for life and “Mimic” for replication. The aim, Khan says, is to replicate the natural human arm through engineering — part of a broader field known globally as bionics.

Roots of an engineer

Born in Karachi in 1997, Khan traces his journey to a childhood shaped by parents who emphasized understanding over rote learning. His early education began at a local school in Karachi’s Nazimabad area, with his mother playing a central role in teaching him at home.

His father, he says, supported him financially and morally, enabling him to pursue engineering with purpose.

As a student, Khan borrowed textbooks, worked independently through advanced material and became known for hands-on experimentation. He later graduated from Ziauddin University and worked as a biomedical engineer in hospital service roles, repairing and maintaining medical equipment.

In 2020, his prosthetic work received a gold medal from Institution of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Pakistan-IEEEP. A year later, an interview about his prosthetic hand went viral, expanding public awareness and demand.

Looking ahead

Khan believes biomedical engineering holds vast potential in Pakistan — from prosthetics and pacemakers to imaging machines and surgical robots. He argues that universities possess adequate resources and that outcomes depend largely on student motivation and passion.

With nearly 60 million amputees worldwide — and about one million in Pakistan — he stresses that prevention and workplace safety are as important as innovation.

For Khan, however, the purpose remains unchanged. His goal is to use locally developed technology to restore dignity and function — and to demonstrate that advanced biomedical innovation is not only possible in Pakistan, but already happening.