Breaking barriers through touch – How Pakistan’s first inclusive Braille is empowering the blind

Perhaps Boltay Huroof's most transformative work involves introducing science, technology, engineering, and mathematics books in inclusive Braille – a first in Pakistan

By MNTV Staff Writer

World Braille Day Special Report

PAKISTAN (MNTV) – For years, Bina Tariq harbored a dream of becoming an Urdu column writer. But as a visually impaired woman in Pakistan, that dream seemed impossible – she couldn’t write in her native language independently. Today, thanks to technology that converts her words into Urdu text, she’s writing regularly for a friend’s blog.

Her column writing ambitions are within reach.

Across Pakistan, Shaheer Ahmed’s father watches his blind son trace his fingers across pages, learning not just words but worlds – understanding how massive a whale is compared to humans, how impossibly long a giraffe’s neck stretches.

Aliya Zaidi, who struggled during the pandemic to teach her visually impaired sister subjects she couldn’t read in Braille, now shares textbooks they can both understand.

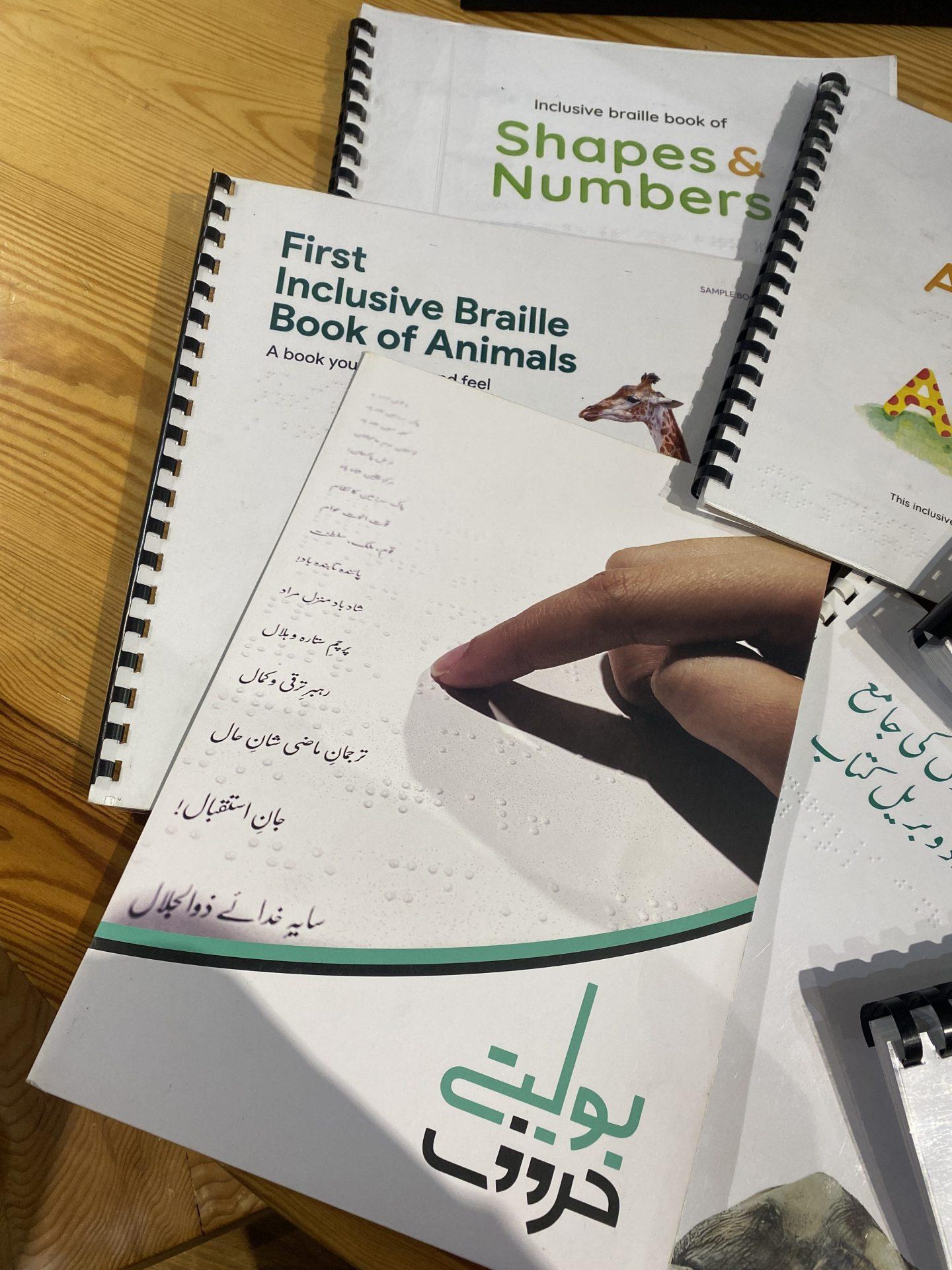

These stories represent a quiet revolution happening in Pakistan’s blind community, led by an organization called Boltay Huroof – meaning “Speaking Letters” – that’s introducing the country’s first inclusive Braille documents and books.

Where conventional Braille failed

“When we started, blind kids in schools had no books,” explains Umar Farooq, CEO of Boltay Huroof.

“International software didn’t support South Asian languages. We needed software that supports both local and international languages so visually impaired people could access knowledge.”

But the problem went deeper than technology. Conventional Braille books, while essential, created an unintended barrier. Family members and friends couldn’t teach blind children because they didn’t know how to read Braille.

Sighted teachers struggled to educate visually impaired students. The very tool meant to enable independence was paradoxically creating isolation.

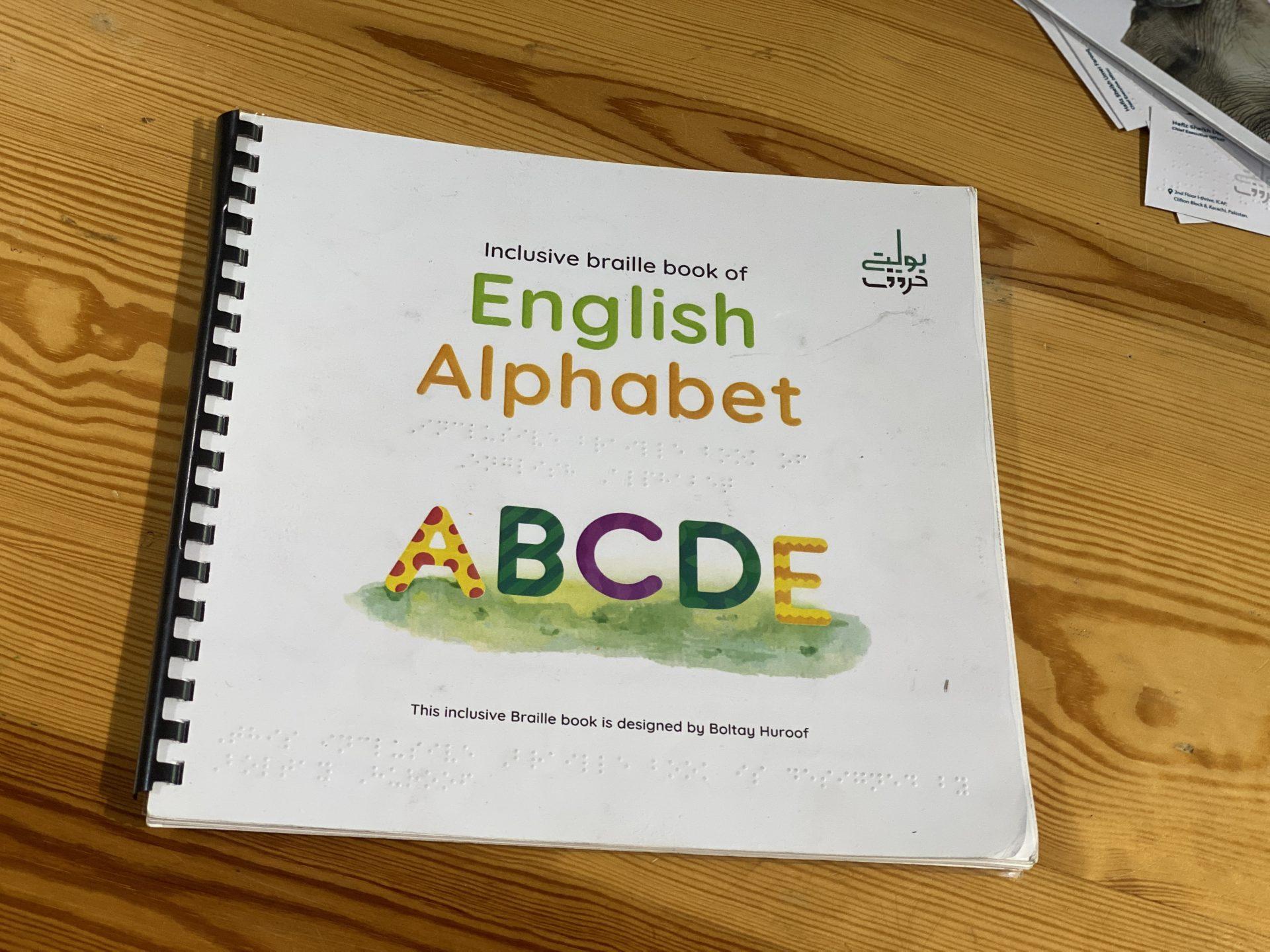

“We created the concept of Inclusive Braille,” says Farooq. “Books that both sighted and blind people can read together.”

This wasn’t just innovation for its own sake. It addressed a fundamental United Nations Sustainable Development Goal: Inclusive Education. Pakistan is a signatory to the UN target of achieving inclusive education for all by 2030.

Conventional Braille alone couldn’t get there. Boltay Huroof stepped in to bridge the gap.

From classrooms to bank-counters

Today, Boltay Huroof has produced over 500,000 Braille documents – and their work extends far beyond education. The organization creates inclusive bank forms, account opening forms, FATCA documents, deposit slips, cheque requisition forms, and credit card applications in Braille.

“We’re not limited to education only,” Farooq emphasizes. “Financial inclusion is critical. We want to make blind people part of the mainstream economy of the country.”

This matters profoundly. As Talha Ali observed, privacy challenges plague visually impaired individuals who must rely on others to read personal documents.

Learning about Boltay Huroof’s Braille banking forms reassured him that steps are being taken to protect their privacy and dignity.

For Pakistan’s estimated 1.5 to over 2 million blind people, the ability to independently open a bank account, fill out financial forms, or manage transactions without depending on others represents genuine empowerment.

Opening STEM doors previously locked

Perhaps Boltay Huroof’s most transformative work involves introducing science, technology, engineering, and mathematics books in inclusive Braille – a first in Pakistan.

Previously, books for visually impaired students were limited to arts and humanities. Blind children who wanted to study STEM subjects simply couldn’t access the materials. Career paths in science, technology, medicine, and engineering remained effectively closed.

“We’ve started introducing science, technology, maths, and STEM-related books,” says Farooq. “We’re using tactile shapes for maths and geometry so these kids can understand concepts through touch.”

Mathematics is currently the foremost priority, with science materials under development.

The tactile elements allow students to feel geometric shapes, understand mathematical concepts spatially, and engage with subjects previously considered impossible for the blind.

Schools that never previously accommodated visually impaired students are now doing so using Boltay Huroof materials.

The inclusive format means sighted teachers can teach blind students without learning Braille themselves, while blind students can study alongside sighted peers.

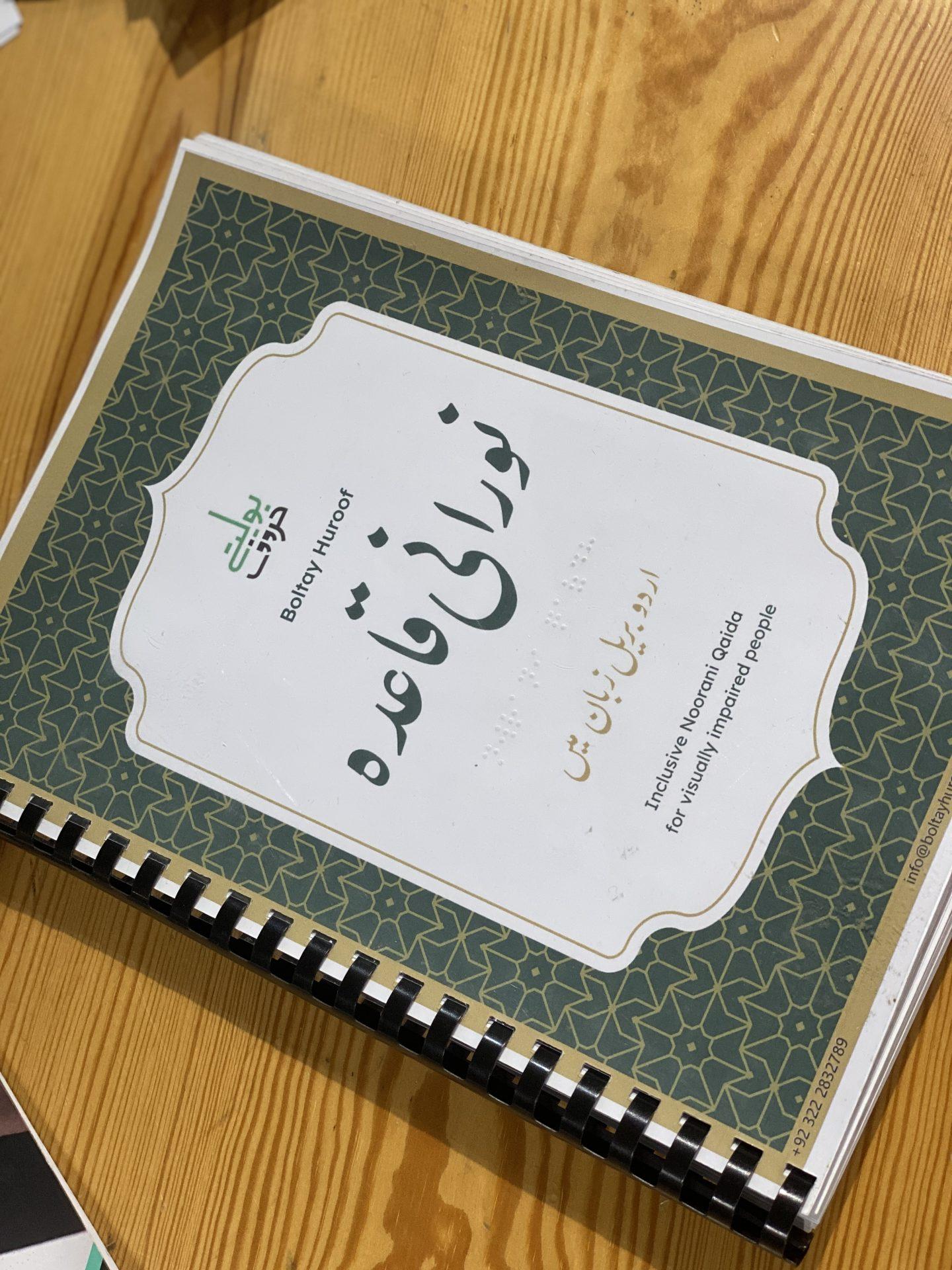

Boltay Huroof has also worked on Quranic learning in inclusive format, bringing sacred texts within reach for all.

Excellence meets accessibility

A persistent problem with conventional Braille books is cost. They’re prohibitively expensive, making it difficult for parents to afford them for their children. Boltay Huroof’s printed inclusive Braille books are comparatively affordable while meeting international standards.

“Our books offer both excellence and accessibility,” Farooq states proudly.

This combination matters. Quality education shouldn’t be a luxury available only to wealthy families. By keeping costs reasonable while maintaining high standards, Boltay Huroof ensures that financial circumstances don’t determine whether a blind child can access learning materials.

The impact ripples through families. The father of Shaheer Ahmed no longer feels helpless watching his son navigate a world he cannot see. Instead, he participates in his son’s education, sharing discoveries about animals and nature through books they can experience together.

A call for systemic change

Yet Farooq recognizes that organizational effort alone cannot create the inclusive society blind Pakistanis deserve. Government action is essential.

“The government must create accessibility for blind people,” he argues.

“But they cannot penalize different sectors for not being supportive to blind people when they haven’t first created necessary awareness and education among the general population. Educate, facilitate, and then penalize if there’s non-compliance.”

It’s a measured, pragmatic approach. Before demanding compliance, create understanding.

Before enforcing penalties, provide tools and training. The goal isn’t punishment but transformation – shifting societal attitudes from seeing blindness as a limitation to recognizing it simply as a different way of experiencing the world.

Blurring the boundaries

Boltay Huroof’s mission statement speaks of “blurring the boundaries between sighted and blind.” In practice, this means creating environments full of opportunities where blind people don’t depend on others for reading documents, where sighted and blind children learn together in the same classrooms, where visual impairment doesn’t dictate career possibilities.

Children with impairments historically attended special schools because sighted people didn’t understand Braille.

Inclusive books create environments where sighted teachers can read and teach visually impaired children alongside sighted students.

This creates social acceptance and inclusion from a very young age.

For Bina Tariq, this means pursuing her writing dreams. For Shaheer Ahmed, it means understanding his world through touch.

For Aliya Zaidi, it means teaching her sister without barriers. For countless others, it means accessing the magic of literature through touch and text, as Helen Keller once described.

As the world marks World Braille Day, Pakistan’s blind community has reason for hope. Louis Braille’s raised-dot system opened doors nearly two centuries ago. Now, in 21st-century Pakistan, those doors are opening wider through inclusive formats that invite sighted and blind people to read together, learn together, and build a more accessible society together.

In Boltay Huroof’s offices, letters are indeed speaking – telling stories of independence, dignity, education, and empowerment. And across Pakistan, fingers are tracing not just dots on pages, but pathways to futures once considered impossible.