Malaysia promotes ‘two kitchens’ strategy amid US-China trade war

Fallout from US President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs is now reverberating across Southeast Asia

KUALA LUMPUR, Malaysia (MNTV) — As tensions deepen between the world’s two largest economies, Malaysia’s trade minister has offered a stark assessment of the challenges facing Southeast Asia: companies will need to build “two kitchens” to survive the escalating US-China trade war.

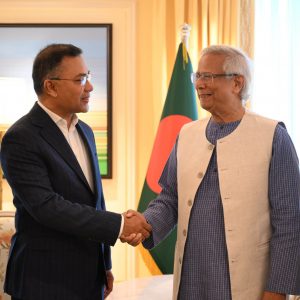

“Our factories, our companies have to start preparing for having two kitchens,” said Trade Minister Zafrul Aziz in an interview with This Week in Asia, referring to the need for businesses to maintain separate production and supply systems for the US and Chinese markets.

The fallout from US President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs—which impose duties of 19% to 49% on a wide range of imports—is now reverberating across Southeast Asia. These tariffs have dampened exports, slowed growth forecasts, and forced regional manufacturers to make difficult strategic choices about where to produce, what to sell, and who their main customers will be.

Zafrul warned that the current decoupling of the two powers is reshaping the global trading landscape in ways that are both commercial and geopolitical. Washington, he noted, has made it clear that it wants to minimize reliance on Chinese supply chains, especially in semiconductors—a sector vital to Malaysia’s economy.

“When we scale up, we’ll have to play both games, both supply chains. We have no choice,” Zafrul said. “The US won’t stop you from trading with China, they’re clear about that. But they don’t want their technology to be compromised. And I think China also feels the same way now.”

The minister said the “two kitchens” concept was no longer hypothetical but inevitable, as both powers move to insulate their strategic industries—even if that means dismantling decades-old supply interdependencies.

Trump is scheduled to attend the upcoming ASEAN Summit in Malaysia, following a visit by his trade representative, Jamieson Greer, in September. During his trip, Greer reinforced Washington’s hardline stance, warning regional manufacturers that they must shift production to the US or face punitive tariffs.

Greer described semiconductor manufacturing as “critical” to US national security, echoing Trump’s earlier threat to impose tariffs of up to 100% on companies that refuse to relocate. The warning carries significant weight for Malaysia, which accounts for about 13% of the world’s advanced chip testing and packaging and aims to expand into higher-value areas like wafer fabrication and integrated circuit design.

Global strategy consultancy Roland Berger noted in a recent report that Trump’s protectionist policies are accelerating a worldwide restructuring of supply chains. “The traditional global supply chain no longer meets regional needs for resilience,” the firm said. “Europe, North America, and Asia are building their own systems, laying the foundation for a multipolar global supply chain.”

China, meanwhile, has already taken the lead in strengthening Asia-centric supply networks, deepening partnerships with Southeast Asian nations as well as Japan and South Korea.

For smaller economies like Malaysia, this shift presents both opportunity and risk. The country must navigate growing fragmentation while balancing its economic ties with both Washington and Beijing.

Reflecting on the challenge, Zafrul acknowledged the limited leverage smaller nations have. “We never expected to stop Trump. Nobody was able to do it — even Singapore,” he said, referring to the neighboring city-state that was hit with a 10% tariff despite having “zero barriers to trade” and running a trade surplus with the US.

“What else can they give?” Zafrul asked. “I’ve engaged my counterpart there, and their boss is very clear — he’s not going to just give up and reduce the tariffs so fast.”